The exhibition included 100 masterpieces of mid-to-late 19th-century French painting from the Musee d’Orsay, a museum in Paris dedicated to the art of the early modern period (1840s through the early 20th century). The exhibition provided a broad context for understanding the roots of Modernism by combining seminal works by innovators such as Courbet, Manet, Cezanne, Monet, and Renoir; Salon painters such as Bouguereau; and artists who moved easily between convention and innovation such as Degas, Fantin-Latour, and Whistler.

The Frist Art Museum was one of only three venues in the world to present The Birth of Impressionism.

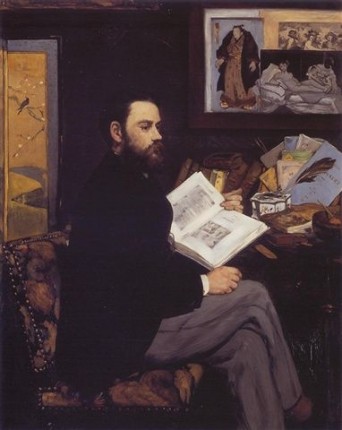

Among the magnificent paintings included in this exhibition were James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Arrangement in Gray and Black, No. 1: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, popularly known as Whistler’s Mother and 15 works by Edouard Manet, including The Fifer and his portraits of Emile Zola, Georges Clemenceau, and Berthe Morisot. There were 11 works by Renoir, including his portrait of Claude Monet, and six works by Degas, including Ballet Rehearsal on the Set.

Content from The Birth of Impressionism Gallery Guide.

In 1874, avant garde artists, including Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro, mounted the first major exhibition by the group that would become known as the Impressionists. Painting scenes of everyday life–parks and avenues, cafes and the countryside near Paris–the Impressionists employed brilliant hues and visible brushstrokes to capture the transient effects of light playing across their field of vision.

This new approach to painting has been widely celebrated for its singular beauty and radical impact on the development of modern art. When presented alongside contemporaneous examples of academic and realist painting as they are in this exhibition, works by the first Impressionists may also be seen as part of a broad spectrum of social, political, and cultural forces that transformed Paris in the 1860s and 70s. Including paintings created in the decades immediately preceding and following the inaugural Impressionist exhibition, The Birth of Impressionism enabled viewers to explore these dynamic crosscurrents as they fostered the development of modern art.

The center of gravity from which the Impressionists broke free was the official Salon of Paris, an annual juried exhibition in which an artist’s reputation could be established or ruined. Favoring themes and stylistic conventions that were taught in established art academies, Salon juries followed a conventional hierarchy in bestowing awards. Highest honors went to history paintings–which included classical, religious, and mythological allegories. Typically, these works’ ultra-smooth surfaces, classically balanced compositions, and muted colors were meant to convey notions of timeless idealism, beauty, and moral clarity. Of lesser merit were genre paintings, then portraiture, still life, and landscape.

Through the middle decades of the 19th century, Paris was the site of conflict between such traditions and the drive to modernity. While the academies protected the established order, artists like Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet questioned Salon taste, believing that art should speak to contemporary life directly and without the gloss of classicism. Courbet and Manet depicted common, even vulgar aspects of life with honesty and directness.

Of the two, Manet–the central figure of this exhibition–is more directly associated with the birth of Impressionism, taking a leading role in the intellectual discourses of the 1860s with other innovators, such as Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Cezanne. Admired by these contemporaries for his facility with paint and his articulate commentary on important issues of the time, Manet was one of many artists who, excluded from the 1863 Salon, participated in an alternate exhibition, the Salon des Refuses. Manet showed works that foretold new directions in painting through the 1860s, earning the derision of the public and critics alike, who failed to understand that he was as much a student of painting’s history as an innovator. Manet counted among his influences seventeenth century Dutch painting and such Spanish masters as Velasquez, whose works were characterized by a stark realism, brooding tones and mysterious dark backgrounds. Like many others, he also absorbed the lessons of Japanese art, celebrated for its harmonious colors and decorative compositions.

A summation of these influences is seen in Manet’s 1868 portrait of the writer and critic Emile Zola. On the wall is a reproduction of Olympia, one of Manet’s own paintings (which Zola deeply admired), which had caused a scandal at the 1865 Salon for its frank depiction of a prostitute. The print from Kuniaki II’s Wrestler series indicates Manet’s interest in Japanese art. The Spanish influence is shown in the print of Velasquez’s Los Borrachos (the drunkards), partly covered by Olympia.

A type of composition known as a “portrait tableau,” Emile Zola follows the tradition of portraiture in providing a likeness, but also represents the figure and props as simply elements in a setting–typically a room’s interior–that is unified through harmonious orchestrations of form, value, color, and space. One of the most famous examples of the portrait tableau was by the American painter, James McNeill Whistler, whose Arrangement in Gray and Black No. 1; Portrait of the Painter’s Mother combines austere realism with the dark values of Spanish painting and the decorative properties of Japanese art. Popularly known as Whistler’s Mother, the work has long been an icon of American culture, admired as a dignified tribute to the artist’s mother. Yet Whistler’s title underscores his interest in going beyond portraiture, to create works in which the visual effects of painting can be compared to the auditory pleasures of music. Just as music had no intrinsic narrative or moral function, Whistler and others of his generation believed in “art for art’s sake,” which could be appreciated for its beautiful arrangements of forms and colors, irrespective of subject.

At the same time that Manet, Whistler, and their contemporaries were pursuing this blend of realism and aestheticism, other painters followed the academy’s penchant for narrative and allegory, but instead of depicting classical subjects, showed contemporary life in rustic settings. Jean-Francois Millet, Jules Breton, and Jules Bastien Lepage painted the countryside and its peasant population to express the value of living in harmony with the land. Millet was also one of the leading artists of the Barbizon School, painters who since the 1830s had traveled to the village of Barbizon and nearby Fontainebleau Forest to capture the ephemeral conditions of light by painting out of doors, or en plein air. In the 1860s, their visible brushstrokes and sensitivity to atmospheric conditions influenced painters like Monet, Renoir, and Sisley, who themselves would take occasional painting excursions to Barbizon.

Back in Paris, the same artists met regularly with Manet and others at the Cafe Guerbois in the city’s Batingnolles neighborhood, seeking to create a new language for depicting modern subjects. Central among the ideas of the Batignolles school was the importance of painting in immediate response to what they saw, whether in the studio, the street, or the fields and forests outside Paris. Although it disbanded with the onset of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the group would form the nucleus of the Impressionists, who used pure colors and fleck-like brushstrokes to convey the transitory effects of light playing across the surface of the landscape or figure. Such works would earn the displeasure of the Salon juries that typically rejected them, and the pleasure of art lovers ever since.

In response to such rejection by the Salon, in 1874 the group staged its own independent exhibition at the photographer Nadar’s studio under the name of the “Societe anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.” All together, the group would mount eight Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, which continued to emphasize the ephemeral effects of light, the importance of seeing and capturing the moment, and the pleasure of pure color harmony.

Despite its radical advances, Impressionism’s frequent formlessness, repetitiveness, and absence of narrative or symbolic content were thought to be too limiting by some members of that first generation, and more of the next. By the early 1880s, Monet had begun moving toward more lyrical colors, with dazzling harmonies and brushwork verging on the dissolution of form into gestural abstraction; Cezanne continued moving toward more simplified volumes and structured spaces, leading toward an abstraction built on intersecting planes and geometric faceting. For his part, Manet absorbed Impressionist influences in the early 1870s. By the mid-1870s into the early 1880s, he had begun taking the Impressionist brushstroke in a new direction, anticipating the vitality and psychological content of the Expressionists working some thirty years later. This can be seen in his portraits of Stephane Mallarme; and Georges Clemenceau, in which paint strokes reveal the inner self as it is written across the surface of the skin.

Among the many giants of early modernism, it was the restless Manet who best signals the passage from the constrictive traditions of the Salon to the expanding language of modernity. The Birth of Impressionism enables us to see this pivotal artist in context, to understand the forces driving this period of momentous change.

This Exhibition was organized by the Frist Art Museum for Visual Arts with gratitude for exceptional loans from the collection of the Musee d’Orsay.

This Exhibition was supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities.

The Frist Art Museum gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the following individuals:

Janet and Jim Ayers

Thomas F. Frist, Jr. Family

Marlene and Spencer Hays

Anne and Joe Russell,

Judy and Steve Turner

K. S. “Bud” Adams, Jr.

Bernice and Joel Gordon

Joey Jacobs

Lynn and Ken Melkus

Andrew Woodfin Miller

Joan and Ben Rechter

Mark Bloom

Amy and Frank Garrison

Joanne and Michael Hays

Jan and Stephen Riven

Delphine and Ken Roberts

Susan and Luke Simons

Joe and Brenda Steakley

Gloria and Paul Sternberg

Julie and Breck Walker

Sissy and Bill Wilson