Drawn from one of the oldest and most significant private collections in Europe, Treasures from the House of Alba: 500 Years of Art and Collecting features works by Goya, Murillo, Rubens, Titian, and more from the splendid palaces of the Alba dynasty in Spain. Co-organized by the Meadows Museum and the Casa de Alba Foundation, the exhibition brings together more than 130 works of art dating from antiquity to the twentieth century. This is the first major exhibition outside Spain of works from the collection of the House of Alba—a prominent Spanish noble family with ties to the monarchy since the fifteenth century.

Highlights include masterpieces of Dutch, Flemish, German, Italian, and Spanish painting, such as Francisco de Goya’s The Duchess of Alba in White and Leandro Bassano’s recently conserved Forge of Vulcan. A map by Christopher Columbus will be on display, along with his list of the people who accompanied him on the Santa Maria on the 1492 Journey of Discovery. Prints and drawings, sculptures, letters, illuminated manuscripts, decorative objects, and tapestries provide further insight into the role of the Alba family in world history.

From the Gallery Guide

Treasures from the House of Alba: 500 Years of Art and Collecting presents more than 130 works of art belonging to one of the most prominent noble families in the political and cultural history of Spain. The House of Alba traces its history back to the Middle Ages and, through commissions, acquisitions, and dynastic marriages, its dukes and duchesses have assembled what is among the most impressive private collections in Europe. The collection features masterpieces of Spanish painting, but its scope is in fact European art from antiquity to modernism and includes historical documents. It therefore tells a story that extends beyond Spain to include many cultural developments that have shaped Europe. From Renaissance Italy to the Age of Exploration, and from the courtly splendor of the Baroque to the high ideals of the Enlightenment, the Alba collection offers a window into European history. This guide calls attention to exhibition highlights and discusses how they reflect their specific cultural moments.

The Italian Renaissance

In the medieval period, artists were considered skilled tradesmen and were subject to the same guild system that organized occupations such as weavers and carpenters. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the period of the Italian Renaissance, artists began to identify themselves as a unique class of craftspeople. Innovations such as linear perspective, which employs mathematics and optics, aligned artists with the sciences, as did practices such as closely studying human anatomy. At the same time, narrative paintings of scenes from classical antiquity, such as Leandro Bassano’s The Forge of Vulcan, and biblical subjects highlighted their affinity with historians and poets.

A painting by Titian (ca. 1488–1576) and his workshop fulfills the Renaissance concept of istoria, which held that artists should vividly convey historical and biblical subject matter through dynamic compositions, gestures, and a mastery of illusionism. The Last Supper appears to take place within a believable space. The lines of the room’s tiled floor are angled toward a single point on the horizon, underscoring the grid structure employed by Renaissance artists to create the appearance of depth. Titian’s abilities as storyteller and dramatist are also evident. He places eleven of the twelve apostles on one side of the table with Christ, emphasizing their solidarity as a group. The lone figure seated opposite is Judas Iscariot; he holds a bag filled with silver, an indication that he has already betrayed Christ. The other apostles express a range of emotional responses to Christ’s pronouncement that one of them will betray him, adding pathos to the familiar biblical scene.

The Age of Exploration

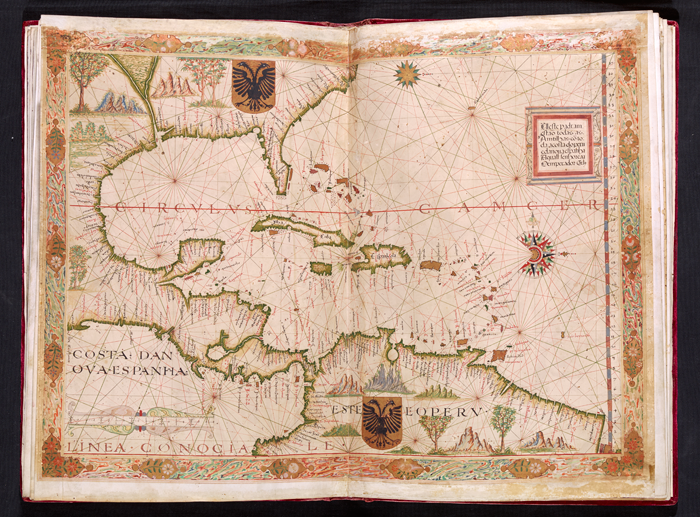

In 1486, the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) first presented his case for a voyage of discovery, with the goal of finding an all-water route to the East Indies, to the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand (reigned 1474–1516) and Isabella (reigned 1474–1504). It took eight years, two more royal audiences, the intervention of a priest, and the fear that another court might hire Columbus for its own exploratory voyage to convince the king and queen to give Columbus the requested ships and supplies. The rest is a familiar story. On October 12, 1492, after two months and eight days at sea, Columbus’s crew spotted land on the western horizon and claimed it for Spain. Columbus’s journey touched off the Age of Exploration, during which major European powers vied for territory and mercantile advantage in the New World. The riches that poured in after the conquest and colonization of the Americas made Spain a global superpower, and the following century would come to be known as Spain’s Siglo de Oro, or Golden Age.

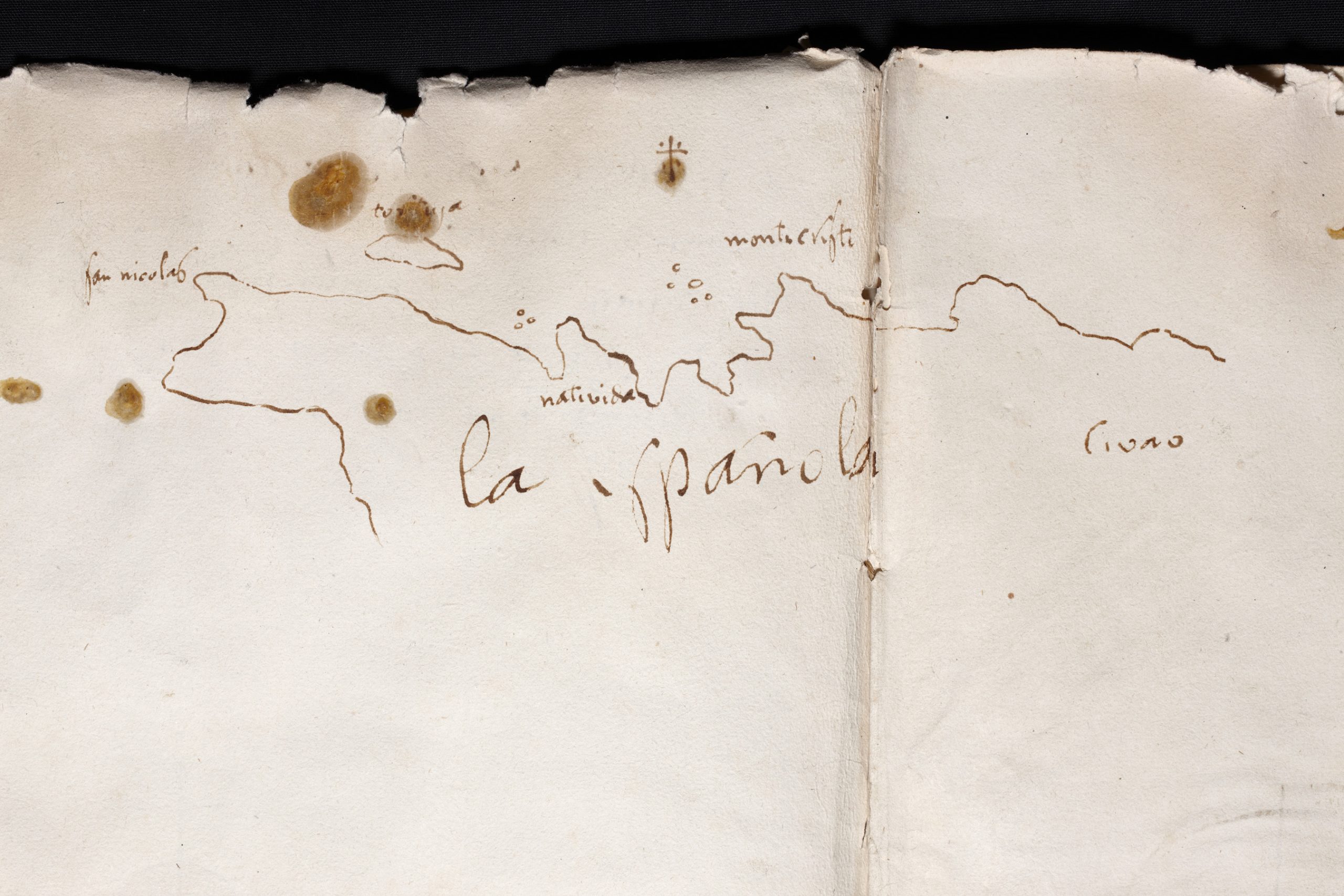

The dukes and duchesses of Berwick and later of Alba have been the custodians of the most significant documents related to Columbus’s voyage ever since one of his descendants married into their family in the early eighteenth century. On view is Columbus’s list of the people who accompanied him on his journey, which has allowed historians to name the forty men and cabin boys who made the historic trip, and a document that is believed to be Columbus’s travel diary. It contains a drawing of the coastline of the island of La Española (Hispaniola, now occupied by Haiti and the Dominican Republic), which may be the first map of a place in the Americas drawn by a European. A royal order signed by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1494, appointing Columbus “admiral, viceroy, and governor of the islands and firm ground of the Oceanic Sea,” is also included. Columbus was eventually dismissed from his post as governor and briefly jailed for his disagreements with the Spanish crown over his proper role in the colonies, but the documents attest to his pivotal role in establishing extended European contact with the New World.

The Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In 1517, a German friar named Martin Luther (1483–1546) nailed his ninety-five grievances against the Catholic Church to the door of the Wittenberg Cathedral, setting in motion the Protestant Reformation and a period of religiously motivated wars that lasted into the eighteenth century.

From1477 until 1609, the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) were part of the Spanish Empire. In 1567, King Philip II of Spain (reigned 1556–1598) sent the 3rd Duke of Alba, don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo (1507–1582), to Flanders to quash a rebellion of Protestants and restore order and religious unity in his territory. The duke’s harsh suppression of the Protestants earned him the moniker The Iron Duke, and he became a symbol of Catholic repression and violence. An allegorical statue in the Alba collection features a serpent with the faces of the Spanish king’s enemies, including the queen of England, the pope, and the elector of Saxony (a leader of Germany and a protector of Lutheranism); the duketries to keep the monster at bay with his staff. Ultimately, he was not successful in stamping out the uprisings in the Low Countries. In 1581, the northern region declared its independence as the Dutch Republic, while Flanders in the south remained under Spanish control.

Paintings in the Alba collection demonstrate the contrasting developments in the visual arts in Catholic and Protestant countries during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. The Old Man and the Maid, by Flemish artist David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690), represents the type of secular genre scenes that appealed to the rising Protestant middle classes in northern Europe. The Crowning with Thorns, by Spanish artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), exemplifies the type of dramatic religious subject matter that Catholic patrons commissioned. Ribera was a follower of the Italian Baroque artist Caravaggio (1571–1610). The dramatic lighting and bold diagonal composition of this painting are characteristic of the kind of theatrical yet naturalistic style that the Catholic Church favored in this period.

Baroque Magnificence

In the seventeenth century, European monarchs competed to bring a handful of famous artists to their courts to paint their portraits and decorate their palaces. The art of the Baroque period is most often described as bold, ornate, and expressive, but at its core it is art in service of royal magnificence. The great kings of the era used grand portraits to create an impressive public image that helped to justify their right to rule in absolute terms.

The Alba collection contains works by Baroque masters connected to the court of King Philip IV of Spain (reigned 1621–1665). Two of Philip’s ancestors, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (reigned 1516–1556) and Empress Isabella (reigned 1526–1539), are depicted by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) in a double portrait that captures the Baroque taste for old and new. The painting is Rubens’s interpretation of an earlier portrait by Philip’s favorite Italian Renaissance painter, Titian, that is now lost. More than a mere copy, the portrait of Charles and Isabella demonstrates how a great seventeenth-century master studied and adapted the aesthetic of a major master who came before him.

Also on view is a 1653 portrait of Philip IV’s daughter, Infanta Margarita, by the Spanish artists Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) and Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (ca. 1611–1667); Velázquez would later feature the princess and her ladies-in-waiting in Las Meninas (1656), the masterpiece housed by the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. Another highlight of the exhibition is a dashing equestrian portrait of the king’s brother, the cardinal infante Ferdinand of Austria. Painted by the Flemish artist Gaspar de Crayer (1582–1669), it exudes Baroque glamour.

Two Women of the Enlightenment

Doña Mariana de Silva Bazan y Sarmiento (1740–1784) married into the Alba family in 1760 and quickly found that she had an ally in her interest in art and literature in her new father-in-law, don Fernando de Silva y Álvarez de Toledo (1714–1776), 12th Duke of Alba. The 12th duke served as ambassador to the French court of King Louis XV (reigned 1715–1774), which meant that he spent much of his time in Paris, the center of the intellectual revolution known as the Enlightenment. There he befriended some of the eighteenth century’s greatest figures, including the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and the writer Voltaire (1694–1778). Both championed individual liberty and rational thought. A letter from Rousseau is in this exhibition.

In 1766, Mariana was admitted into the Royal Academy of San Fernando, an institution that taught painting, drawing, and sculpting and administered annual exhibitions. She later became its director, an unusual role for a woman of the period. A portrait of her by the German painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), an important figure in the revival of neoclassicism during the Enlightenment period, captures her direct gaze and intelligent countenance.

Mariana’s daughter, doña María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva y Álvarez de Toledo (1762–1802), 13th Duchess of Alba, was immortalized in paint by another of the Enlightenment’s most prestigious artists, Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) of Spain. Like her mother and grandfather, Cayetana was intellectually curious and artistically adventurous. Her grandfather taught her philosophy and foreign languages at home rather than sending her to a convent school, and as an adult, she surrounded herself with artists and scholars.

Goya painted the duchess many times, and their close friendship has sparked rumors of intimacy that have persisted through the centuries. On the cover of this guide, the duchess wears a white gown; its high empire waist and graceful simplicity reflect the vogue for classical antiquity in the late eighteenth century. The dress is ornamented with a brilliant red sash and bow and complemented by a coral necklace, as well as matching bows in her hair and on her dog. The duchess’s expression is one of self-possession and firmness, yet she seems natural and unconstrained, displaying none of the obvious trappings of social status. This tension between apparent ease and strong will makes it a portrait not just of one woman but of the character of the Spanish Enlightenment.

The House of Alba in the Twentieth Century

Don Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart (1878–1953), 17th Duke of Alba, and his daughter, doña María del Rosario Cayetana Fitz-James Stuart y de Silva (1926–2014), 18th Duchess of Alba, steered the Alba family through the twentieth century, expanding and protecting the family’s cultural legacy and art collection. The duke acquired portraits of his historically significant ancestors and Old Master paintings related to the Spanish monarchs they had served. Cayetana expanded the Alba collection into new territory by adding French Impressionist paintings.

Both father and daughter were painted by the Spanish artist Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945). The art historian María Dolores Jiménez-Blanco has noted that Zuloaga was viewed by certain international collectors and critics in the first half of the twentieth century “as a modern merging of Velázquez, Goya, and El Greco.” His affinity for defining a particularly Spanish aesthetic steeped in art history made him perfectly suited to capture Jacobo and Cayetana as members of a modern family with a very old name.

Zuloaga’s depiction of Cayetana combines the most prestigious, traditional portrait type, the equestrian portrait, with the markers of a twentieth-century childhood. Cayetana sits astride a gentle-looking pony in a grassy field with a collection of toys and the family dog. The inclusion of Mickey Mouse in the foreground is one of the earliest representations of Disney’s iconic character in fine art. This melding of classical portraiture conventions and pop culture perhaps presaged something of the 18th duchess’s vivacious character. While she maintained her role as the figurehead of one of Spain’s most distinguished families, she was also known for her love of lively Spanish entertainments such as bullfighting and flamenco.

Today, Cayetana’s eldest son, don Carlos Fitz-James Stuart, 19th Duke of Alba, continues his family’s legacy of collecting and is the guardian of the House of Alba’s treasures for future generations.

Megan Robertson, associate curator of interpretation

The exhibition was co-organized by the Meadows Museum and the Casa de Alba Foundation. A generous gift from The Meadows Foundation made this project possible.

This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Exhibition gallery

Thank you to our exhibition supporters