Collection of James E. Petersen Jr., Houston, Texas

1955 Lincoln Indianapolis. Collection of James E. Petersen, Jr. Image © 2016 Michael Furman

1955 Lincoln Indianapolis. Collection of James E. Petersen, Jr. Image © 2016 Michael Furman

1955 Lincoln Indianapolis. Collection of James E. Petersen, Jr. Image © 2016 Michael Furman

1955 Lincoln Indianapolis. Collection of James E. Petersen, Jr. Image © 2016 Michael Furman

Sponsored by: Roger and Genma Holmes

Italian carrozzerie were greatly interested in the potential of the American market after World War II. Felice Mario Boano was a mild-mannered, talented stylist with proven management ability. Eventually forced out of Carrozzeria Ghia by an aggressive and abusive Luigi Segre (Boano wanted to concentrate on the Italian market; Segre wanted to work for American carmakers), he established Carrozzeria Boano in 1953 with a partner, Luciano Pollo. The elder Boano was assisted by his son, Gian Paolo, who added a youthful design perspective to his father’s more traditional approach; Gian Paolo was twenty-four years old when a mysterious insider named John Cuccio at Ford Motor Company offered to introduce the Boanos’ work to key decision makers in Dearborn.

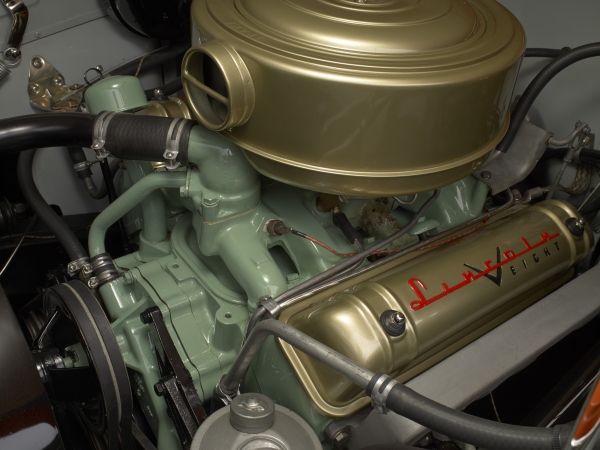

A new Lincoln chassis was procured and Gian Paolo began crafting a prototype for the 1955 Turin show. Gian Paolo’s design for the Indianapolis was influenced by an Indy 500 pace car and jet aircraft. Carrozzeria Boano’s craftsmen worked a tubular frame and yards of sheet metal into a dramatic shape that owed little to previous Lincoln styling efforts. The resulting coupe boasted a very long hood, which extended downward to a vestigial front bumper and thence to an essentially grille-less “bottom-breather” air intake. This car’s prominent front fenders and quad headlamps swept rearward into large vertical air scoops that defined the leading edge of the rear fenders.

The scheme to attract American attention succeeded, as Ford offered the Boanos a ten-year contract—but Mario Boano reported this development to Fiat and subsequently agreed to instead establish Centro Stile, Fiat’s in-house styling department. The Indianapolis was doomed from the outset. Lincoln was simultaneously developing the Continental Mark II and had no need for another personal coupe. Despite its name, the Indianapolis was more boulevard cruiser than sports car, even though the side badging with a checkered-flag motif, a black-and-white checkered interior, wire wheels, and bold flame-orange paint all hinted at a competition car. Henry Ford II took possession of the Indianapolis for a time, and some believe he later gave it to Hollywood heartthrob Errol Flynn. Whatever its history with Flynn may be, the Indianapolis passed through several owners after the actor’s death. It suffered an interior fire and then was partially disassembled and stored for decades. Following its rebirth, Boano’s masterpiece won top awards at several concours, including the prestigious annual event at Pebble Beach.

—Adapted from the exhibition catalogue essay by Ken Gross